Bayesian versus frequentist statistics

Read time: 7 minutes

Last edited: Dec 13, 2024

Overview

This guide explains the difference between Bayesian and frequentist statistics, both of which are available in LaunchDarkly's Experimentation framework.

There are two major branches of statistics: Bayesian and frequentist. Most people don’t need to know the difference, but for the curious, this guide provides a high-level overview of the difference with respect to Experimentation. Some of the distinctions are rather technical and subtle, but here we try to highlight the key differences. This section is an introduction and is primarily focused on these two statistical methodologies in the context of Experimentation. It is not an in-depth comparison of the two.

To learn more about LaunchDarkly's Experimentation feature, read Experimentation.

To learn more about the details of the statistical methodologies used in LaunchDarkly's Experimentation feature, read Experimentation statistical methodology for Bayesian experiments and Experimentation statistical methodology for frequentist experiments.

Comparison of Bayesian and frequentist statistics

In Bayesian statistics, if you collect enough data, your results will be nearly identical to your results using frequentist statistics. One way to think about this is that Bayesian statistics and frequentist statistics only differ significantly in two ways: in smaller sample sizes and in interpretation.

These are both reasons why we offer Bayesian statistics as an option for our Experimentation framework. One hurdle for some experimenters is that it’s difficult to run experiments when you don’t have a large sample size. Examples of this are areas of a site with low traffic, end user types that have small populations, or business-to-business (B2B) companies. Bayesian statistics allows you to make valid inferences when those sample sizes are small, whereas often frequentist statistics will not provide statistical significance in those scenarios.

Overall, we believe that a Bayesian approach is best for some of our customers because of its effectiveness with smaller sample sizes and its intuitive interpretation.

Bayesian and frequentist probabilities

If you have run experiments before, you might have heard of concepts like "statistical significance" and "p-values." These are concepts from frequentist statistics. It’s called frequentist statistics because probabilities in frequentist statistics refer to the long run frequencies of a process. In other words, how a statistics method performs when repeated many, many times. For example, if you roll a 6-sided die one million times, you will roll a 1 about one in six times, a 2 about one in six times, and so on. The probability of rolling a 1 is 1/6, or 16.7%.

Bayesian statistics, on the other hand, takes probabilities to refer to our degree of belief in a particular outcome. A frequentist would say the probability of rolling a 1 on a 6-sided die is 1/6, because that’s the long-run frequency. However, a Bayesian would say the probability of rolling a 1 on a 6-sided die is that your degree of belief that it will come up 1 is 16.7%.

To understand these different interpretations of probability, the two branches of statistics use slightly different methods.

Bayesian and frequentist modeling

So, how does it work? Bayesian statistics uses the same data as frequentist statistics, but with a slight twist. We can understand Bayesian statistics by thinking about where it shares data and statistical models with frequentist statistics.

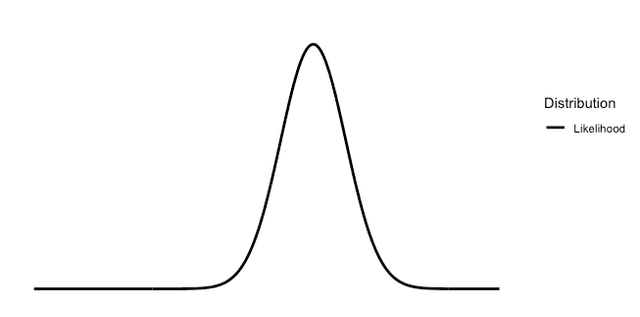

In frequentist statistics, you have some data. For simplicity, we're representing it here as a distribution called the "normal" or "Gaussian" distribution.

Here is a graph representing a normal distribution in frequentist statistics:

In frequentist statistics you use properties that we know exist over the long run for samples collected in a certain way which follow, or have parameters that follow, this distribution.

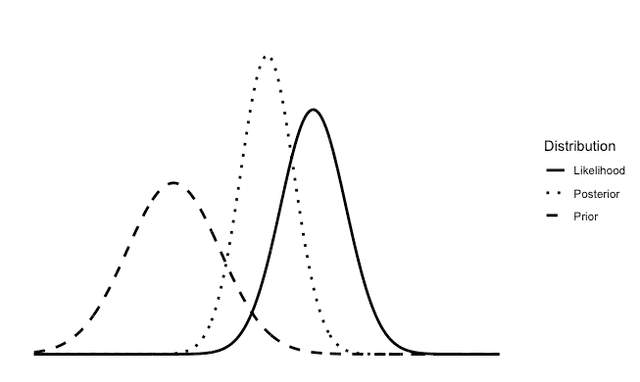

In Bayesian statistics we work with the same data. However, we also include prior beliefs we have about the data. For example, let’s suppose the data above is the heights of adult individuals in the United States. If, before collecting the data, we believe that 90% of the heights will fall between five feet and six feet, then we can start with that prior belief. After we collect the data, we can combine the data with our prior beliefs and the Bayesian updating process will provide what’s called a "posterior distribution." The posterior distribution represents our updated beliefs after combining prior knowledge with the observed data.

Here is a graph representing a posterior distribution in Bayesian statistics:

Both the frequentist and Bayesian graphs use the same collected data. Bayesian statistics just incorporates prior beliefs you might have. Frequentist statistics also incorporates prior beliefs about the data, but in a very different sense. You have to pick the appropriate statistical model and process based on beliefs you have about the data, but it doesn’t incorporate prior beliefs in the same way that Bayesian does.

Bayesian and frequentist methods

The methods and interpretations of probability for frequentist and Bayesian statistics are pretty different. For instance, because frequentist statistics is focused on long run frequencies, its foundations are around mathematical guarantees over time.

In frequentist statistics, "statistical significance" means if you ran an A/B experiment an infinite number of times, and A and B weren’t actually different, then you are guaranteed that a certain percentage of the time, your statistical test will tell you that there is a difference.

You need to specify this difference, which is the significance level, or "alpha," of the test. The alpha is the the upper limit for the false positive rate, or "Type I error." If the test significance has an alpha of 5%, then it is guaranteed that your statistical test will show a significant difference of, at most, 5%, when there is no true difference for a two-sided test. This is the null hypothesis of your two-sided test.

To be interpreted differently, Bayesian statistics requires you to specify your belief about what the outcome will be before the experiment. This is called a "prior belief." Given these prior beliefs, plus the data, Bayesian statistics can guarantee that the probabilities that it produces are exactly the degree of belief you should have.

Both methods assume that the data collection and aggregation methods are free from bias and both involve assumptions and prior beliefs, but used in different ways. Any time you choose a statistical model under either framework, you are using your prior beliefs about the data generating process. How the statistical branches use assumptions and prior beliefs is different.

When to use Bayesian versus frequentist statistics

Now that we have explained the difference between frequentist and Bayesian statistics, this section offers a brief overview of when to use each approach in our Experimentation platform.

Priors and sample size

Bayesian statistics incorporate information from both observed data and prior distributions. The choice between frequentist and Bayesian approaches often depends on prior assumptions and sample size:

- Bayesian: Better suited when the treatment variation is expected to have a small impact on the metric of interest or when the sample size is limited. Bayesian priors can provide meaningful insights in these cases.

- Frequentist: Ideal if you want results to rely solely on the data without priors, particularly when you have a large sample size.

Interpretability

The interpretability differences between Bayesian and frequentist include:

- Bayesian:

- Offers intuitive probabilistic insight. Bayesian provides direct probabilities for outcomes, such as the probability that a variation beats control or is the best among available variations.

- Has a natural decision framework. Bayesian outputs align with intuitive decision-making, offering a clear understanding of uncertainty and the degree of belief in an outcome.

- Frequentist:

- Offers binary results. Frequentist focuses on determining whether results are "statistically significant" or not, based on a p-value.

- Does not directly provide probabilities about one variation being better than another.

Other advantages and disadvantages

When deciding between the two statistical approaches, consider the following advantages and disadvantages about each method:

- Bayesian:

- Offers flexibility and avoids issues like peeking and multiple comparisons. To learn more, read Statistical Modeling, Causal Inference, and Social Science. Unlike frequentist methods, Bayesian results remain valid every time they are updated, even with incremental data points.

- Provides probabilities such as "probability to beat control" and "probability to be best," allowing for informed decision-making under uncertainty.

- Does not offer error rate guarantees. While Bayesian methods do not directly control Type I error rates, they provide valuable insights into measurement uncertainty and support decision-making through probabilities, such as "probability to beat control" and "probability to be best."

- Frequentist:

- Is commonly used, is the standard in statistical literature, and is widely understood.

- Offers error rate control, directly controlling Type I error rates through the significance level.

- Comes with some risks, such as analyzing results mid-experiment, called "peeking," multiple comparison problems, and misinterpreting results in A/B/n tests.

Conclusion

To summarize, we recommend the following:

- Use Bayesian methods when flexibility, incremental data updates, and interpretability of results in terms of probabilities are more critical, especially in small-sample or low-traffic scenarios.

- Use frequentist methods when you need standardized error control, have sufficient data, and want results independent of prior assumptions.

Both methods have their strengths, and the choice depends on the specific needs and context of your experiment. That’s why LaunchDarkly offers both options in its Experimentation platform.

For more details on the statistical methodologies used in LaunchDarkly’s Experimentation feature, read:

- Experimentation statistical methodology for Bayesian experiments

- Experimentation statistical methodology for frequentist experiments

Your 14-day trial begins as soon as you sign up. Get started in minutes using the in-app Quickstart. You'll discover how easy it is to release, monitor, and optimize your software.

Want to try it out? Start a trial.